Music is often described as the universal language, a bridge between hearts and minds, transcending boundaries of culture and time. But what if music is more than just art or emotion? What if it is science—rooted in principles as exacting as mathematics itself? Pythagoras, the ancient Greek philosopher, is widely regarded as the father of music theory. His mathematical approach to intervals and scales helped shape the very foundation of Western music. However, as Leonard Bernstein, the legendary composer and conductor, suggested in his famous Harvard speech *The Unanswered Question* (1973), the science of music reaches deeper than we might imagine.

### Pythagoras and the Theory of Music

Pythagoras is known for many things, but his contributions to music are particularly striking. He was the first to discover that harmonious sounds could be produced by simple mathematical ratios. By dividing a vibrating string at specific intervals, Pythagoras was able to produce the notes that would later form the major scale—the very backbone of Western music. These intervals, and the relationships between them, can be measured, calculated, and explained in mathematical terms. In essence, music is a form of auditory mathematics.

But as precise as this science is, Bernstein pointed out something profound: there’s something in music that can’t be captured by formulas or theory alone.

### Bernstein’s Insight: Feeling Beyond Calculation

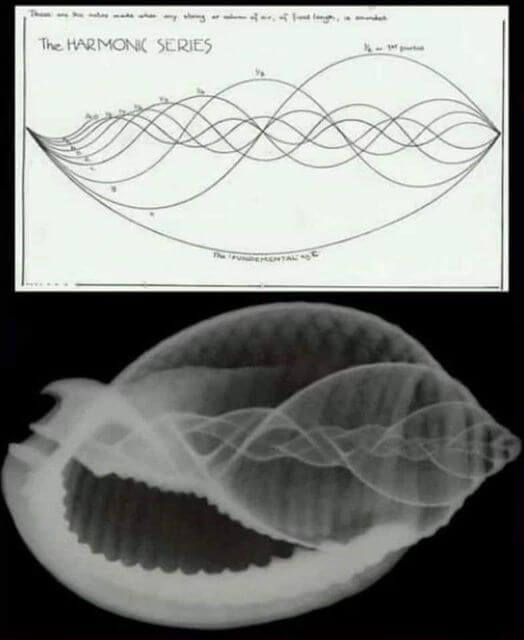

In his 1973 speech, Bernstein delved into the harmonic series, a natural phenomenon that underpins much of music theory. He demonstrated how the harmonic overtones in sound waves are structured and how they form the basis for our understanding of musical intervals. But while he could explain the scientific foundation of music, Bernstein acknowledged that there is something intangible, something beyond numbers and theory, that music brings to life.

He made a notable observation about Indian music, specifically the concept of the *Raaga*. While Western music relies on fixed scales and harmonic progressions, Indian music—with its intricate and emotionally resonant Raagas—offers something far more dynamic and experiential. As Bernstein remarked, “What we calculate and explain or try to explain through the music theory of Pythagoras, only appreciators of Indian music can feel it.”

### The Mystery of Raaga: Music That Speaks to the Soul

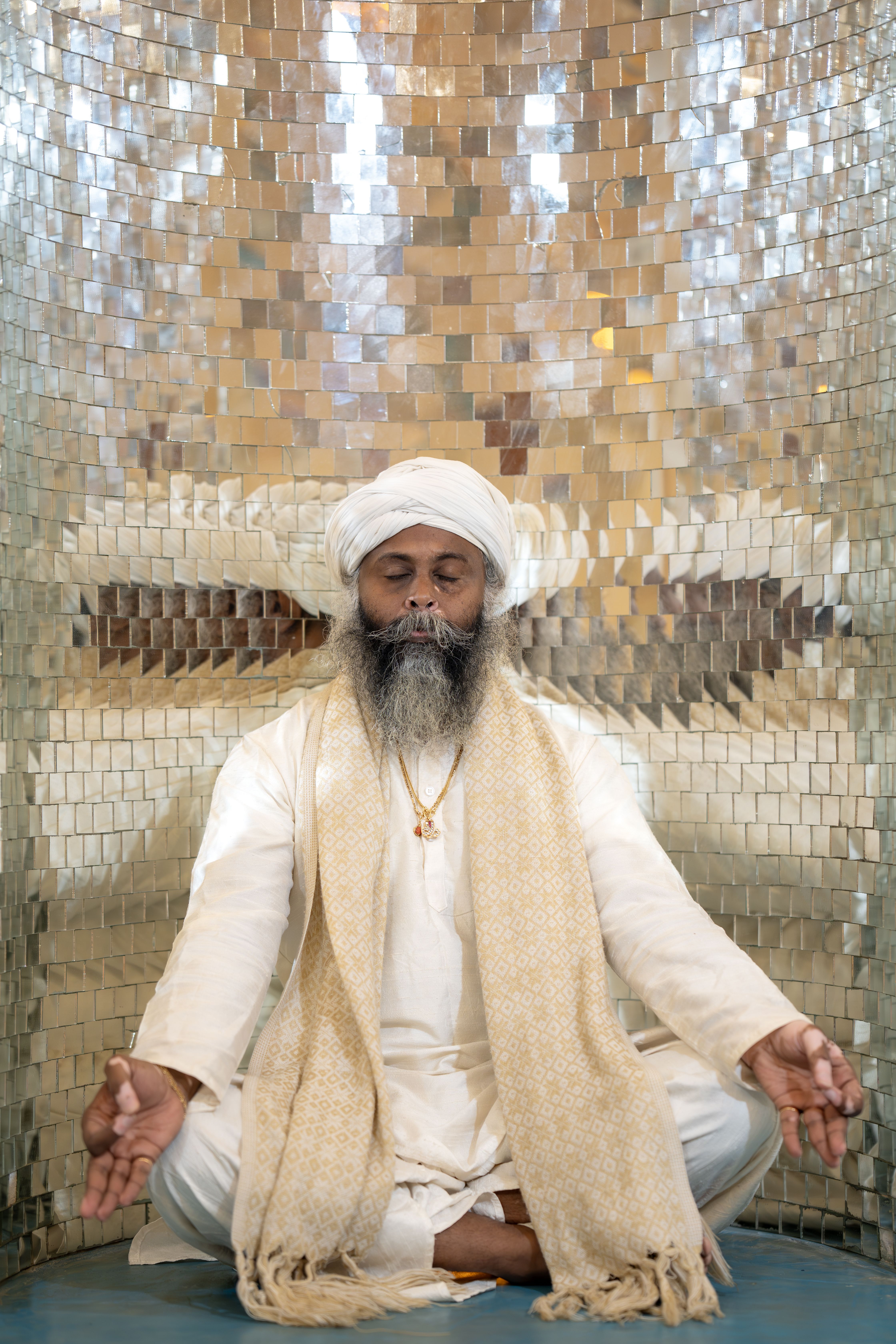

A Raaga is not just a scale or a series of notes; it’s a mood, a feeling, a deep emotional narrative expressed through sound. In Indian classical music, each Raaga evokes a specific emotion or atmosphere, whether it’s joy, sorrow, love, or devotion. But more than that, Raagas have the power to convey these emotions in a way that transcends intellect. If you are unable to appreciate or resonate with the Raaga’s subtlety, it might lull you to sleep. But if you feel its essence, it will stir something deep within you, something that defies explanation.

Bernstein’s insight speaks to a truth that runs through much of the world’s ancient music traditions: music is not just sound arranged mathematically—it is a force that moves the soul.

### Panchajanya: The Conch Shell and the Harmonic Series

After observing the similarity between the harmonic series and the spiral of a conch shell, one can’t help but marvel at the deep, intrinsic connection between the natural world and music. The harmonic series, which forms the basis of musical sound, and the swirling patterns of a conch shell both follow the same geometric principles. They are expressions of the same fundamental truths about nature.

In Hindu mythology, the conch shell is a symbol of divine sound and is closely associated with the god Vishnu. His conch, Panchajanya, is said to emit a sound that resonates through the cosmos, symbolizing the beginning and continuation of life. The sound of the conch is a reminder of the deep connection between sound and the divine.

The realization that music, particularly Indian classical music, may have its roots in something as ancient as the sound of the conch shell offers a humbling perspective. It suggests that our ancestors understood the power of music—its ability to connect us with something greater—long before Pythagoras formulated his theories.

### Music’s True Purpose: Connecting with the Divine

Pythagoras once said, *“The highest goal of music is to connect one’s soul to their Divine Nature, not entertainment.”* This quote encapsulates the deeper essence of music that Bernstein touched upon in his speech. While Western music theory can explain the structure of music, the true purpose of music goes beyond mere enjoyment or intellectual understanding. It’s about reaching into the core of our being and connecting with something higher.

Indian music, through the use of Raagas, exemplifies this principle. Each Raaga serves not just to entertain but to transport the listener to a higher state of consciousness. It is a journey, not a destination, and the notes are the guideposts along the way.

### Conclusion: The Science and Spirit of Music

Music, at its core, is both science and spirit. Pythagoras gave us the mathematical foundation that allows us to understand how sound works, but the essence of music—the way it moves us, stirs our souls, and connects us to the divine—goes beyond formulas. Bernstein’s observation about the power of Raagas reminds us that some aspects of music can only be felt, not explained.

From the harmonic series to the sound of the conch shell, music is an ancient, natural force that has been with us since the dawn of time. It is not merely entertainment; it is a way to connect with our deeper selves and with the world around us. In the end, the true beauty of music lies in its ability to bridge the gap between the tangible and the intangible, between science and spirit, between the earthly and the divine.

0 Comments